Time for a story! Specifically, it’s time to talk about my initial idea for Albion and where it came from.

Time for a story! Specifically, it’s time to talk about my initial idea for Albion and where it came from.

Welcome to our next character study piece, this time about Orion Sisley.

Orion is the stroppiest character I’ve ever written. He has good cause – especially in Illusion of a Boar when he’s coming out a completely horrific six months or so. For those not familiar with the term, it’s slang. The term became more common in the 80s, but is dated to use starting in 1943. It means rebellious, with an edge of ‘just plain difficult’, sometimes for baffling reasons. (Here’s the Etymology Online entry.)

This post contains plot spoilers for Illusion of a Boar, Orion’s romance. (Stop at “The War” of you want to avoid those.)

Welcome to our Idea to Book post for The Magic of Four, which just came out at the beginning of May. (This means that from now I’ll add a new Idea to Book post a few weeks after the book comes out. But you won’t have a long string of them.)

The Magic of Four is also the last book in the Land Mysteries series, which explores three themes during the Second World War. Those are a range of different kinds of relationships in our lives. It’s also about the land magic, and how Albion responds to the Second World War. You can see all three of those here, in various ways.

The Magic of Four has everything you might hope for in a school story. There are snippets of classes, finding friends, dealing with student problems. And of course, because it’s Schola, it’s got magical sports (pavo and a dash of bohort), secret societies, and all the implications of a magical school.

As I’ve noted, I do have plans for three romances. Ursula Fortier (Leo’s older sister) will have hers in 1947, Edmund Carillon (Ros’s older brother) in 1948, and Claudio Warren (in his 40s, and close to both Leo and Avigail) in 1950. Those will let me tie up some loose threads on other ongoing questions about the land magic, living in post-war Albion, and the Council. Learn more about my plans.

(more…)It seems a good time for an update on neurodiverse characters in my books (the last one was back in 2021.) April is one of the months celebrating neurodiversity (Autism Acceptance Month), and there was a recent extensive rec post on /r/romancebooks on Reddit for romances with neurodiverse characters.

As I did in 2021, we’re going to go at this by character (alphabetically by first name), since many relevant characters appear in multiple books. My goal with writing has always been to reflect a wide range of experiences of the world like me and many of my friends. And that includes people who don’t always get to be the ones on adventures or getting a happy ever after romance.

There are a number of other characters in my books you might reasonably read as neurodiverse. I’ve mentioned a few at the end of the post that Kiya and I have discussed back and forth, but some of this is in the eye of the beholder. Reader perception is important too!

Just want to explore some books? Here are all the titles that particularly feature a neurodiverse character.

Showing books 1-16 of 16

Period: Edwardian

Romance: F/F, Late in life romance, Closed door, Lesbian

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Period: 1920s

Romance: M/F, First relationship, Demisexual, Bisexual

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Period: 1920s

Romance: M/F, First relationship, Late in life romance, Closed door, Demisexual

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Period: 1920s

Romance: M/F, First relationship, Late in life romance, Demisexual

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Period: 1920s

Romance: M/F, Established relationship, Closed door

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Period: Second World War

Romance: M/F, M/M/F, Established relationship

Content notes: Click here to reveal

Showing books 1-16 of 16

You can also find more of a number of these characters in various of the extras I’ve written and shared.

One of the things I’ve thought about a lot is the interaction between architecture and magic in Albion.

Now, first, I am by no means a specialist in this sort of thing! But besides having lived in a range of places, I’ve done a little bit of college coursework that covered buildings. I’ve been generally been interested in how spaces adapt and change over time.

It’s time for the Ideas to Book for Illusion of a Boar. There’s so much I love about this book, both these four men and women and what it says about the Albion of the Second World War.

(This does contain a spoiler about Cammie in the last section…)

I’m excited to be part of FaRoFeb this year. That stands for Fantasy Romance February, and it’s a promotion with a number of moving pieces. There are tons of different events planned, including 250+ books available for $0.99 US on February 1st. (That’s tomorrow, when I’m posting this.) There are also author spotlights, a panel discussion, a giveaway of a book a day between February 1st and Valentines Day on February 14th, and more.

Find out all the details at the FaRoFeb 2024 site including how to follow FaRoFeb on your social media of choice and how to sign up for the newsletter to get the book giveaways.

And if you follow FaRoFeb on social media (please do!), you’ll see me spotlighted on February 8th.

Three of my books will be on sale for $0.99 USD (and the equivalent elsewhere) through February 15th as part of FaRoFeb.

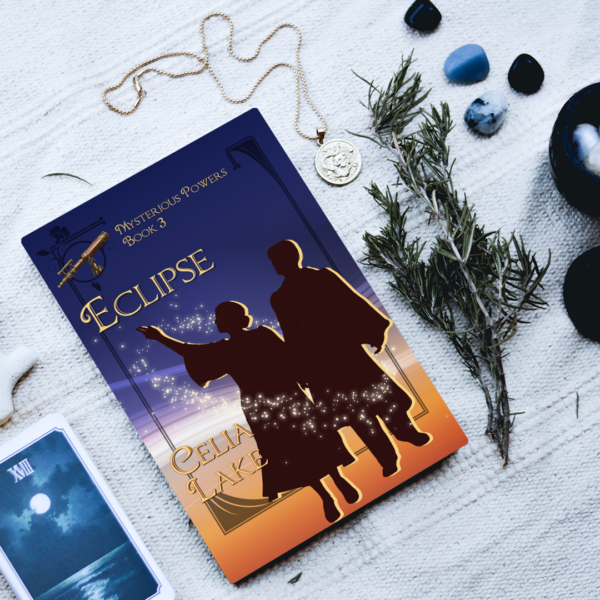

They are Sailor’s Jewel, Pastiche, and Eclipse. All three are set in Albion, the magical community of Great Britain that is the setting for all my books. They’re a mix of history, fantasy, romance, and a puzzle or mystery to solve. (In FaRoFeb terms, they fall into the gaslamp category.)

Read on to learn more about all three books!

(more…)It’s time for summer reading challenges where I am. Whatever time of year it is for you, I thought it might be fun to do a round up of some reading challenges. Some of these come from libraries, and some come from other groups. I’m still waiting on my local library’s challenge (out on June 17th), but I’m thinking about how I’d like to nudge my reading a little bit.

(To be honest, a lot of it has been research reading, one way or another, and I would like to mix it up, and also just read more.)

Here are some different challenges to check out. You can also check your local library systems (a lot of libraries put something together for adults, as well as for kids and teens.) If there’s nothing up yet, check back later in June, my local public library isn’t launching theirs until the 17th.

(more…)I love all my books – and all my point of view characters – but Thesan and Eclipse are particularly near and dear my heart. (I love Isembard too, mind you.) This staffroom romance at a magical school has a special place in the series, too.

I grew up in the US, but with British parents. Every year, my father would go off to spend a week or so in England – for research, to see shows in the West End (he was a theatre professor), and to see friends. He’d come back with his suitcase half full of books, many of them for me.

There’s a whole glorious literature of children’s school stories in British children’s lit. The ones I grew up on were mostly Enid Blyton’s St. Clare’s and Malory Towers books, and the Chalet School books (there are many, and the first half or so are set in a school in the Austrian Tyrol, but run on a British girls school model, before it moves due to the Second World War.)

But there are many many other books of that type and certainly many references to the boarding school experience. The houses, the rivalries between them (even when you’re put in them in purely pragmatic ways), and the many things that students get up to when they’re not right under a teacher’s nose (and sometimes when they are) were all part of the tapestry for me.

A little later in my life, I spent the last two years of high school at a private boarding school (in the US sense). There were a lot of things I loved about it, like many of my classes, the music, the various events and performances on campus. And there were many things I found incredibly challenging, both in terms of an immense and intellectual demanding workload and on a social level. We had massive amounts of homework (5 to 6 hours a night), everyone felt like they were under a lot of pressure to excel. And the social dynamics could be hellish if things weren’t going your way.

And then I spent a decade working in a private day school in Minnesota. Much less of the strong identification based on which dorm you lived in, but it gave me a look at that environment from a teacher – or in my case, librarian’s – point of view. I got to sit in on a lot of conversations about how you balance a range of classes, both in any given year and across a given student’s time in the school. I heard a lot about which kids seemed to have it all, but were really struggling, and which were blooming with a bit of support. More on this in a minute.

From 2007 to 2015 (before the more recent revelations), I was part of a long running Harry Potter alternate universe project, startign very much as a dystopia and moving toward a more hopeful end. It played out in online journals with (for the last three years of the project), the same 12 people writing and plotting across about 90 characters. It taught me a tremendous amount about how to write across a span of time and a wide range of characters, and it also posed a number of questions around worldbuilding.

Among other things, how on earth the Hogwarts class schedules work with the stated number of teachers without manipulating time.

There’s a reason that when I started thinking about this writing idea I had, the first two things I did was to figure out some baselines for demographics (how many people total in Albion, then broken down by ages and education). And then I did a class schedule for Schola. Which admittedly works somewhat more on a “do a bunch of work on your own and your teacher gives feedback” model than US (or modern UK) systems, but is functional.

Thesan in particular is very much a result of that project, as was my wanting to play with the dynamics that come out in Isembard and Alexander. Most of all, I found myself wanting to spend more time looking at what it meant to set up a magical school that made pedagogical sense to me, that made sense in terms of historical development of the teaching of magic, and that had biases and preferences, but on a more complex level.

Alchemy and Ritual magic are the two most respected magical specialities (along with the various magics that go into duelling, for those that like that sort of thing). But almost no class exists in a void: you need Time and Place (the advanced astronomy class focusing on locational and chronological magics) to manage some kinds of advanced ritual preparation and planning, for example, or certain alchemical potions and mixtures.

Similarly, I have a lot of thoughts about what it means to have houses that are based on magic, and what the different house magics might affect. We’ve seen some of these discussed briefly, but there will be more coming in the 1946-1947 school story that’s the last book in the Land Mysteries series, where our protagonists are in four different houses (Bear, Fox, Horse, and Salmon), and we’ll get to see more of the different implications of the house magics.

In general terms, Fox, obviously, is the socially preferred house, but the others all have their proponents and for good reasons.

This brings us more or less tidly to astronomy. For many many centuries, astronomy – the observation and analysis of the movement of stars and planets – was closely woven with astrology, which ranged from calendrical systems around which rituals were based to magical implications, to divinatory. If all you know of astrology is personality focused, there’s a lot more forms of astrology out there!

In Albion, what Thesan teaches is on the more scientific end of the scale, in the sense of “Can we reproduce this effect?” Various alignments of the stars (as seen from our particular spot in the universe, as she points out), have some impact on different kinds of magic. Using these techniques to time a ritual, expose materia to particular conditions, or make relationships between time and space can all be powerful tools.

Astronomy is also one of the four pillars of the quadrivium, a set of sciences that drive the world and help us make sense of it. I couldn’t use this in the book, but there’s a modern description of them that talks about them as pure numbers (arithmetic), numbers in space (geometry), numbers in time (music), and numbers in time and space (astronomy).

Every student at Schola takes Trivium (the arts of rhetoric, composition, and generally being able to use your words well), and then can take one to all four of the Quadrivium classes. All first years also have a class session every day where the Quadrivium teachers teach the basics of their particular fields (emphasis on what you need to know for other magical skills), so everyone gets at least some broad exposure.

And as Thesan points out, astronomy has a lot of other implications for how you look at the world, about seeing what’s there by what you can’t see and how it affects things.

Finally, but by no means least, I really wanted to write about the complexities of being a teacher, and trying to be a good one. Like I said above, I worked at an independent high school for twelve years. The last eighteen months or so, I was the teacher librarian, and so had a homeroom, advising duties, and so on as well as being a librarian.

The thing I’d already known – but I learned even faster – was that there’s always dozens of things going on in a school that you only know about tangentially. No matter how good a teacher you are, you cannot keep up with the individual private lives of even a couple of dozen students, never mind several hundred. (The school I worked at was about 400 in grades 9-12, so larger class size than Schola, but not that many more students.)

There were some kids I got to know really well, and still miss (and sometimes wonder about) and those conversations were pretty wide ranging. What they were up to in the arts, in sports, in their classes, what they were considering for college. There are a bunch where I had very specific kinds of conversations with them – they’d check in on the daily trivia question in the library, for example. Or where I knew they liked these books a lot. But I often didn’t know a lot about their classes, their sports. Sometimes I’d pick up bits and pieces sitting with other teachers at lunch time.

But there were also plenty of kids where I maybe knew their name and that was about it. For whatever reason, we hadn’t connected on something specific, they weren’t the ones who hung out in the library whenever possible, they had other places to be.

Sometimes the kids I knew needed a lot more time and attention – the chaos of a friend breakup meant they needed somewhere quiet to figure out what to do next. Or they were stressed, and needed somewhere to hang out that wasn’t associated with grades directly. Or where I’d look the other way if they listened to music with headphones on.

(I still have the librarian death glare that can shut up people being too noisy at twenty feet or better, but I also believe strongly that if you’re in a library minding your own business, you should get to listen to music on headphones if you want to. Or read what you want to, even if it’s not what you ‘should’ be reading.)

And sometimes I knew something was up with them, but I wasn’t the right person to help (or to help more than tracking down someone they knew and trusted a lot more).

Thesan and Isembard are right there in that mess during Eclipse. There are some students both of them know fairly well, and more where one or the other knows them, but not both. There are also just plain a lot of students! Thesan has some advantage, because she’s one of the only teachers (the other three Quadrivium teachers are the others) who actually teaches everyone in an academic course, however briefly.

We have more to come of Schola in 1946-1947. That’s the school story, and one of the student protagonists and point of view characters in that is Leo, Thesan and Isembard’s son and younger child, who has lived his whole life at Schola. I’m very much looking forward to sharing more of that in due course! It’ll be out in May of 2024.

Curious? Eclipse has all this, and quite a lot more! If you want more about Schola (and Thesan and Isembard), Chasing Legends (found in Winter’s Charms) takes place on their first anniversary. There’s also an extra, With All Due Speed, available via my newsletter, that covers their engagement and wedding. Later on, they appear in Best Foot Forward, and there’s more of both of them to come in the Land Mysteries series.

I had a fabulous time working with the map designer who did my previous two maps to do a map of Schola.